enrique marty: allegories

Past exhibition

Overview

Enrique Marty, a Spanish Allegory

During the corona pandemic humanity was forced to take distance, to disconnect. Spanish artist Enrique Marty (°1969. Salamanca) did the exact opposite and this his was the inspiration for Allegories, Marty’s first solo exhibition in Antwerp. ‘I wanted to get closer, to humanity. It seemed to me that the time had come to connect with what it had all been about all along. In Allegories I came to the realisation that everything up to then was just leading up to this exposition. A feeling of coming home.

Press release

Looking at an everyday scene and thinking to yourself: this could be an Enrique Marty. It happened to me this summer, at the Belgian seaside. A man and a woman sitting across from each other at a table in the parlour of their dinery, heads bent. They’re peeling shrimp. The man smiles broadly when a passer-by, an habitué, walks by. It’s a forced smile, a mechanically constructed smile to cover up the severity of the underlying misery. The woman on the other hand remains unwavering. Her begrudging smile takes place inside, muttering.

Or the image of the man in a Parisian café reading Dostoyevsky and bursting into tears. Quietly, restrained. A grimace on his face, like a cramp.

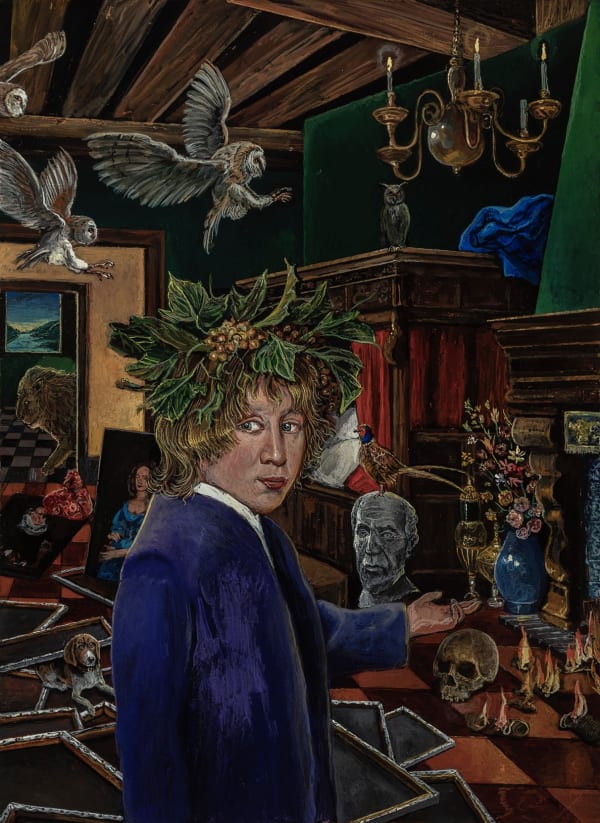

Enrique Marty’s works are never dull. He’s intrigued by what people feel and is relentlessly wondering where inner tensions, emotions and shadows come from. In the past Marty would register the gloomy picture of man (and humanity) in the tragedy that is his life, the image of the individual who dares to break free from the crowd to look for his own truth, his Ithaca. For Allegories however, he blurs the border between past and present, between death and life. It feels a lot like dreaming. Dreaming and painting appear to be inextricably linked and in his ‘dreams’ he travels through time or, better yet, through humanity – there is no time. Painters from the past are treated as contemporaries. And even though what we see in these scenes is less repulsive, more serene, than what we’re used to from this artist, something is filled with dramaturgy…

Little Enrique grew up in Salamanca, surrounded by everything he likes to be surrounded with. A city full of churches and ornaments, sculptures and tapestries. A daily encounter with a gothic or baroque history packed with symbolism. Sitting on the steps of the San Esteban cloister, he merely needed to lift up his head to be swept away by a Raphael-like tableau and identify with the characters. The idea of being able to be a different person in every room grows on him. ‘Even a church is like a theatre’, he says, ‘a room filled with dramaturgy’. In this theatre he surrenders to the polyphony within himself and his thinking – you’re not one determined person, authentic and true to yourself, but always ‘something different’. This realisation is the key to resonance. ‘Man needs to direct his focus on others. The threat of getting locked up in an identity is always there, but if you enter the social world the same way Goya did, or Dali, you’ll see different guises and life forms all around us; people, animals and things speaking to us, calling on us to answer’.

Everything has something to share with us, if it is seen for what it truly is. Watching is an enigmatic human ability to see meaning in everything. What do we need to know to understand the artist’s unique work and thinking? In first instance it’s amazement that directs our gaze, amazement over something that is yet to be revealed and clarified, to distil all riddles comprised in an infinitely mysterious work of art. The allegory in Enrique Marty’s work is an intricate metaphor tracing through the whole oeuvre and through the whole exhibition space. From start to finish an incredible curiosity makes us look at Marty’s ‘bride’ as eagerly as at Van Eyck’s Arnolfini couple.

Enrique Marty’s skill however, is to make us realize we don’t have to understand everything. ‘Symbolism invites interpretation’, he explains. ‘every scene (or every room) in the Non-melancholic scenes is a spiritual experience’. How someone experiences the image and its symbolism depends on the nature of the viewer.

To get closer to the life of the Old Masters, the artist stays, as long as necessary, in a room in the historical centre of Antwerp. On the corner of a table he paints in the light of the Flemish Primitives. There we see the artist with his brush, his painter’s eye focused on the panel. To enhance the canvas’ luminosity, he applies colour pigments with egg yolks and oil, a technique Van Eyck also used. Beauty is in the right proportions. He knows all the skills of his masters. Now it comes down to finding the right colour intensity to suggest depth in the landscape.

To really approach history, he visits the places these Old Masters used to frequent. He appropriates the decors of the Rubens House, the Maidens’ House Museum, the Snijders&Rockox House and the Museum Mayer van den Bergh, but also the Rubens hall of the KMSKA serve as a decor in numerous of paintings. ‘I transform the rooms or record them digitally to reinterpret them later’ Marty explains.

It’s no coincidence Antwerp has become Enrique Marty’s home away from home. A biography by Rubens which Enrique bought together with his older brother, lies at the heart of his fascination with the Old Masters. Enrique was barely six years old. Like a little determined professor he examined the whole period between the 13th and 17th century, read everything about Antwerp ‘the mysterious’ and about the mysterious man and hermit Rubens. ‘I discovered baroque was hardcore in the thriving décor of Antwerp’s middle ages’.

We know the baroque dynamic staging Rubens applies in his oeuvre. The light-dark contrasts and other theatrical effects to enchant the viewer. The abundant use of ornaments, preferably in gold, as a reference to the celestial light and eternity. But baroque is also about resistance. The artist who dares to draw outside the lines, damned or called to self-creation to start from an existing story and experiment with something we call form. Here it’s all about ‘creating oneself through creating form’. This most definitely sounds like resistance. Behold the condition humain, made of unrealities – there is no true identity, there is only man trying to assign qualities to himself.

The artist delves deeply into memento mori and symbols referring to hope and life. The bronze sculpture of the girl with the somewhat fearful look in her eyes holding the (seemingly) writhing fish for example, or the scene of the woman with the crystal ball. Another scene shows a young Antoon Van Dijck with a flying owl above his head, his hand pointing at something – at what? Or the young Rubens with the wreath of flowers, a finger in front of the mouth, suggesting we don’t need to know everything…

Symbolism is also to be found in the sculptures that have claimed a place in the exhibition space. ‘they don’t present themselves’, Marty emphasizes, ‘they represent’. Some have a name or wear folkloric attire. Each of them wears an offering as a tangible present, a sign of connection. The sculptures on the pedestals in the basement are painted in recognisable baroque colours. They, too, embody that which we stand for.

Enrique Marty’s work trembles, seeks communication, observation, resonance, correspondence, or whatever you want to call getting on the same wave length with another person. All those myths show man as a social being, searching and probing for connection. They show how man is sensitive to the failures of social interaction: they show how man, unfinished as he is, has to try over and over again to connect and thus acquire form.

Kathy de Nève, November 2022.

Installation Views

Works

-

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022 -

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022 -

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022 -

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

-

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022 -

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022 -

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022 -

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

-

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022 -

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022 -

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022 -

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

-

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022 -

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022 -

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022

Enrique Marty, Non-melancholic scenes (series), 2020-2022 -

Enrique Marty, Gifts (series) - Gift 2, 2022

Enrique Marty, Gifts (series) - Gift 2, 2022

-

Enrique Marty, Gifts (series) - Gift 4, 2022

Enrique Marty, Gifts (series) - Gift 4, 2022 -

Enrique Marty, Gifts (series) - Gift I, 2022

Enrique Marty, Gifts (series) - Gift I, 2022 -

Enrique Marty, Gifts (series) - Gift 3, 2022

Enrique Marty, Gifts (series) - Gift 3, 2022 -

Enrique Marty, Offerings (series) - Ana, 2022

Enrique Marty, Offerings (series) - Ana, 2022