benjamin moravec: jenseits der vierten wand

Das ist die Sehnsucht: wohnen im Gewoge und keine Heimat haben in der Zeit.That is longing: to live in the waves and have no home in time.Rainer Maria Rilke

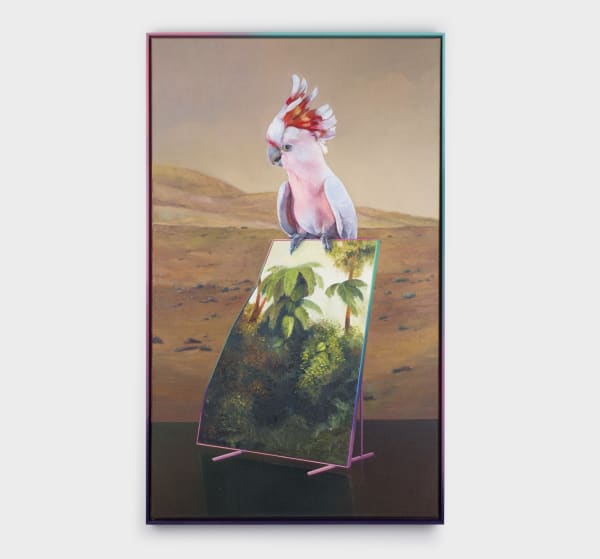

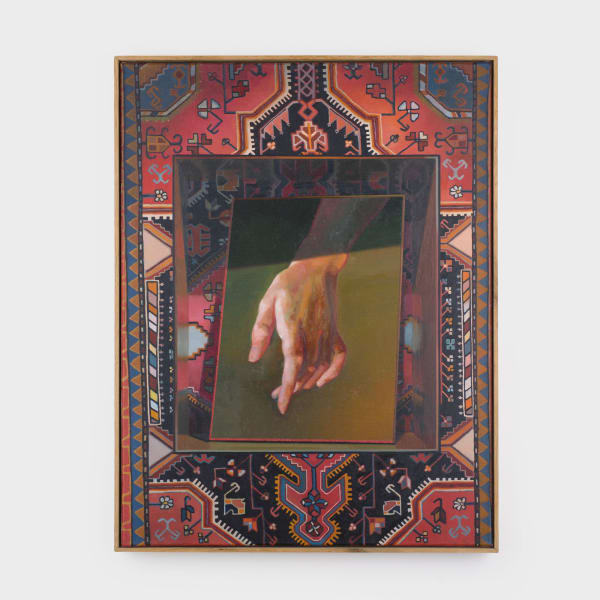

Foreground, middle and background become “dimensions” of a collage that is as mental as it is material: the space of the painted image breaks through that of reality and vice versa. Illusions become real and reality shows itself to the viewer as an illusion. The motif of the grid surface seems to represent the boundary between reality and another world – the gaze cannot get a grip on grid patterns anyway.

The visitor who looks at this total installation in such a way begins to comprehend what the artist could mean by Jenseits der vierten Wand (on the other side of the fourth wall)… because the ‘fourth wall’ was originally a theatre term for the imaginary wall between the audience and the stage, between the hall and the drama. The spectator can look through this wall at the actors on the stage, but the spectators are invisible to the actors. It was the French Enlightenment philosopher Denis Diderot, known from his “Encyclopédie”, who first described the fourth wall in his “Discours sur la poésie dramatique” from 1758: “So whether you write or play, do not think more about the viewer than if he didn’t exist. Imagine a large wall on the edge of the stage that separates you from the parterre: play as if the curtain will not rise.” The concept of the fourth wall became the norm at the time of the Enlightenment, on the eve of modernity, and would always remain so: the players, who had addressed the audience for centuries and had involved the spectator in the game, turned to each other now. The spectator became the consumer of a perfect illusion.

This modernisation and the accompanying rationalization of the world of experience, evoked melancholic reactions in a great number of early Romantic artists, and Benjamin Moravec’s paintings seem to follow this tradition. His colour palette and masterful touch, two technical aspects that always tell more about a painter than his subjects, breathe the atmosphere of early Romanticism. It is no coincidence that his style is reminiscent of Courbet, a painter who, like Moravec, stood with one foot in the romantic approach to life and with the other already in the realism of the exact, photographic image. In one of his most famous paintings L’atelier du peintre (1855), Courbet portrays himself, working on a second painting that could almost be by Moravec, in the midst of people from his surroundings, against the fictitious background of yet another canvas; fiction and reality with the artist in between… The work was given a subtitle that could also apply to Jenseits der vierten Wand: “Allégorie réelle déterminant une phase de sept années de ma vie artistique et morale”.

The sunsets, exotic trees and deep vistas that Moravec cites also further betray the influence of the American early Romantic painters of the so-called Hudson River School: these artists painted the American wild natural landscapes which were disappearing in real life, with a scientific attention to the realistic representation of nature. But the landscapes were completely fictional, idealised compositions.

On the one hand, Benjamin Moravec, as a contemporary romantic, is looking for his place as a painter in today’s infinite stream of images. From this he brings out those images that keep haunting his mind because they stir up a romantic longing in him for another world. Exotic birds, landscapes too beautiful to have ever existed, an ideal garden or a cool and dark water surface. But on the other hand, this self-contained desire, this ‘Sehnsucht’ is also disturbed. The model is ironically clarified as a construction, nature and the trees in the background are set pieces, artificial light disturbs the evening twilight. Paradise doesn’t seem real. A flame eats its way through the fourth wall, from the other world to ours.

We live in the modern, fragmented age of the digital image, where nothing is what it seems; in which anything can be anything. Jean Baudrillard – another French, post-modern thinker, called our contemporary living environment a “hyperreality” in which images are no longer a representation – or denial – of reality but “simulations” of reality. The original is non-existent and the image is there to cover that up.

The works in Jenseits der vierten Wand bathe in an atmosphere of ambiguity. Something is always hidden from view or shrouded in shadow. A number of works evoke a longing for peace, ecstasy or for a kind of absorption in the other or in nature; in still other works that desire is veiled by a kind of voyeuristic loneliness or existential doubt. In a work with the telling title The day we lost the daylight, a child looks away from a billboard in the middle of a surreal, empty landscape. Is daylight a metaphor for innocence – just like the child in the work itself? For a lost, blissful naivety, for an unambiguous, “real” existence? Is the child anonymous and, as a mysterious creature by definition, does it symbolize the distance between human beings? The same may also apply to the greatest work in the exhibition, the enigmatic An apocalypse for happy people II. The same alienation also emanates from Belsazzar on Mars II. In An apocalypse for happy people I an image of a young girl blowing a bubble gum raises questions about innocence and subjectification. All the works in this exhibition appear to be exponents of the same, essentially romantic, themes.

Benjamin Moravec, like so many of his modern fellows, is tormented and nourished by the desire to escape into a dream world and by the realisation that we can only exchange one reality for another. The romantic tension that he interprets in Jenseits der vierten Wand is recognisable to everyone and his quest yields enigmatic, enchanting works.

Text by Dries Verstraete, 2021.

-

Benjamin Moravec, An apocalypse for happy people II, 2021

Benjamin Moravec, An apocalypse for happy people II, 2021 -

Benjamin Moravec, An apocalypse for happy people I, 2020

Benjamin Moravec, An apocalypse for happy people I, 2020 -

Benjamin Moravec, Belshazzar on Mars I, 2021

Benjamin Moravec, Belshazzar on Mars I, 2021 -

Benjamin Moravec, Belshazzar on Mars II, 2021

Benjamin Moravec, Belshazzar on Mars II, 2021

-

Benjamin Moravec, Etude, 2019

Benjamin Moravec, Etude, 2019 -

Benjamin Moravec, The day we lost the daylight, 2020

Benjamin Moravec, The day we lost the daylight, 2020 -

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2020

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2020 -

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2020

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2020

-

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2020

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2020 -

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2020

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2020 -

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2020

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2020 -

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2021

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2021

-

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2021

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2021 -

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2021

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2021 -

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2020

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2020 -

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2021

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2021

-

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2020

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2020 -

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2020

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2020 -

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2021

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2021 -

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2021

Benjamin Moravec, Untitled, 2021